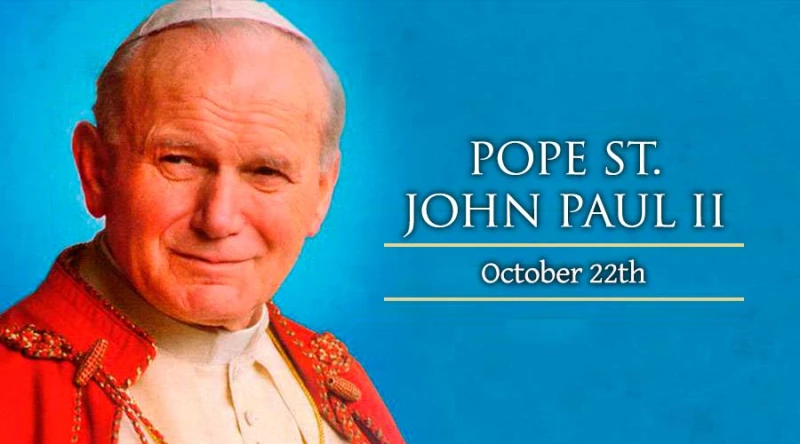

Pope Saint John Paul II

Pope Saint John Paul II

Feast date: Oct 22

Saint John Paul II is perhaps one of the most well-known pontiffs in recent history, and is most remembered for his charismatic nature, his love of youth and his world travels, along with his role in the fall of communism in Europe during his 27-year papacy.

Karol Józef Wojtyla, known as John Paul II since his October 1978 election to the papacy, was born in the Polish town of Wadowice, a small city 50 kilometers from Krakow, on May 18, 1920. He was the youngest of three children born to Karol Wojtyla and Emilia Kaczorowska. His mother died in 1929. His eldest brother Edmund, a doctor, died in 1932 and his father, a non-commissioned army officer died in 1941. A sister, Olga, had died before he was born.

He was baptized on June 20, 1920 in the parish church of Wadowice by Fr. Franciszek Zak, made his First Holy Communion at age 9 and was confirmed at 18. Upon graduation from Marcin Wadowita high school in Wadowice, he enrolled in Krakow’s Jagiellonian University in 1938 and in a school for drama.

The Nazi occupation forces closed the university in 1939 and young Karol had to work in a quarry (1940-1944) and then in the Solvay chemical factory to earn his living and to avoid being deported to Germany.

In 1942, aware of his call to the priesthood, he began courses in the clandestine seminary of Krakow, run by Cardinal Adam Stefan Sapieha, archbishop of Krakow. At the same time, Karol Wojtyla was one of the pioneers of the “Rhapsodic Theatre,” also clandestine.

After the Second World War, he continued his studies in the major seminary of Krakow, once it had re-opened, and in the faculty of theology of the Jagiellonian University. He was ordained to the priesthood by Archbishop Sapieha in Krakow on November 1, 1946.

Shortly afterwards, Cardinal Sapieha sent him to Rome where he worked under the guidance of the French Dominican, Garrigou-Lagrange. He finished his doctorate in theology in 1948 with a thesis on the subject of faith in the works of St. John of the Cross (Doctrina de fide apud Sanctum Ioannem a Cruce). At that time, during his vacations, he exercised his pastoral ministry among the Polish immigrants of France, Belgium and Holland.

In 1948 he returned to Poland and was vicar of various parishes in Krakow as well as chaplain to university students. This period lasted until 1951 when he again took up his studies in philosophy and theology. In 1953 he defended a thesis on “evaluation of the possibility of founding a Catholic ethic on the ethical system of Max Scheler” at Lublin Catholic University. Later he became professor of moral theology and social ethics in the major seminary of Krakow and in the Faculty of Theology of Lublin.

On July 4, 1958, he was appointed titular bishop of Ombi and auxiliary of Krakow by Pope Pius XII, and was consecrated September 28, 1958, in Wawel Cathedral, Krakow, by Archbishop Eugeniusz Baziak.

On January 13, 1964, he was appointed archbishop of Krakow by Pope Paul VI, who made him a cardinal June 26, 1967 with the title of S. Cesareo in Palatio of the order of deacons, later elevated pro illa vice to the order of priests.

Besides taking part in Vatican Council II (1962-1965) where he made an important contribution to drafting the Constitution Gaudium et spes, Cardinal Wojtyla participated in all the assemblies of the Synod of Bishops.

The Cardinals elected him Pope at the Conclave of 16 October 1978, and he took the name of John Paul II. On 22 October, the Lord’s Day, he solemnly inaugurated his Petrine ministry as the 263rd successor to the Apostle. His pontificate, one of the longest in the history of the Church, lasted nearly 27 years.

Driven by his pastoral solicitude for all Churches and by a sense of openness and charity to the entire human race, John Paul II exercised the Petrine ministry with a tireless missionary spirit, dedicating it all his energy. He made 104 pastoral visits outside Italy and 146 within Italy. As bishop of Rome he visited 317 of the city’s 333 parishes.

He had more meetings than any of his predecessors with the People of God and the leaders of Nations. More than 17,600,000 pilgrims participated in the General Audiences held on Wednesdays (more than 1160), not counting other special audiences and religious ceremonies [more than 8 million pilgrims during the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000 alone], and the millions of faithful he met during pastoral visits in Italy and throughout the world. We must also remember the numerous government personalities he encountered during 38 official visits, 738 audiences and meetings held with Heads of State, and 246 audiences and meetings with Prime Ministers.

His love for young people brought him to establish the World Youth Days. The 19 WYDs celebrated during his pontificate brought together millions of young people from all over the world. At the same time his care for the family was expressed in the World Meetings of Families, which he initiated in 1994.

John Paul II successfully encouraged dialogue with the Jews and with the representatives of other religions, whom he several times invited to prayer meetings for peace, especially in Assisi.

Under his guidance the Church prepared herself for the third millennium and celebrated the Great Jubilee of the year 2000 in accordance with the instructions given in the Apostolic Letter Tertio Millennio adveniente. The Church then faced the new epoch, receiving his instructions in the Apostolic Letter Novo Millennio ineunte, in which he indicated to the faithful their future path.

With the Year of the Redemption, the Marian Year and the Year of the Eucharist, he promoted the spiritual renewal of the Church.

He gave an extraordinary impetus to Canonizations and Beatifications, focusing on countless examples of holiness as an incentive for the people of our time. He celebrated 147 beatification ceremonies during which he proclaimed 1,338 Blesseds; and 51 canonizations for a total of 482 saints. He made Thérèse of the Child Jesus a Doctor of the Church.

He considerably expanded the College of Cardinals, creating 231 Cardinals (plus one in pectore) in 9 consistories. He also called six full meetings of the College of Cardinals.

He organized 15 Assemblies of the Synod of Bishops – six Ordinary General Assemblies (1980, 1983, 1987, 1990, 1994 and 2001), one Extraordinary General Assembly (1985) and eight Special Assemblies (1980,1991, 1994, 1995, 1997, 1998 (2) and 1999).

His most important Documents include 14 Encyclicals, 15 Apostolic Exhortations, 11 Apostolic Constitutions, 45 Apostolic Letters.

He promulgated the Catechism of the Catholic Church in the light of Tradition as authoritatively interpreted by the Second Vatican Council. He also reformed the Eastern and Western Codes of Canon Law, created new Institutions and reorganized the Roman Curia.

As a private Doctor he also published five books of his own: “Crossing the Threshold of Hope” (October 1994), “Gift and Mystery, on the fiftieth anniversary of my ordination as priest” (November 1996), “Roman Triptych” poetic meditations (March 2003), “Arise, Let us Be Going” (May 2004) and “Memory and Identity” (February 2005).

In the light of Christ risen from the dead, on 2 April a.D. 2005, at 9.37 p.m., while Saturday was drawing to a close and the Lord’s Day was already beginning, the Octave of Easter and Divine Mercy Sunday, the Church’s beloved Pastor, John Paul II, departed this world for the Father.

From that evening until April 8, date of the funeral of the late Pontiff, more than three million pilgrims came to Rome to pay homage to the mortal remains of the Pope. Some of them queued up to 24 hours to enter St. Peter’s Basilica.

On April 28, the Holy Father Benedict XVI announced that the normal five-year waiting period before beginning the cause of beatification and canonization would be waived for John Paul II. The cause was officially opened by Cardinal Camillo Ruini, vicar general for the diocese of Rome, on June 28 2005, and he was beatified May 1, 2011.

On April 27 , 2014 he was canonized by Pope Francis during a ceremony in St. Peter’s Square.

In an April 24 message sent to the Church in Poland, Pope Francis gave thanks for the great “gift” of the new Saint, saying of John Paul II that he is grateful, “as all the members of the people of God, for his untiring service, his spiritual guidance, and for his extraordinary testimony of holiness.”

Reading 1 Isaiah 11:1-10 On that day, a shoot shall sprout from the stump of Jesse, and from his roots a bud shall blossom. The spirit of the LORD shall…

Click here for daily readings I remember going to Mass at my parish during Advent and hearing Father sing “Prepare Ye the Way of the Lord” (from the musical Godspell)…