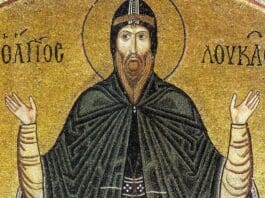

Saint Luke the Younger was born on the Greek island of Aegina, the third child among seven siblings, to a family of farmers. Due to attacks by Saracen raiders, his family was forced to relocate to Thessaly. Here, young Luke worked in the fields and shepherded sheep, showing early signs of deep charity that often puzzled his parents.

Known for his exceptional kindness, Luke regularly gave away his food to the hungry and did not hesitate to offer his clothing to beggars. He even went as far as scattering half of the seeds meant for his family’s fields into the fields of the impoverished neighbors. Despite the prosperity of their crops, his parents disapproved of his actions.

Following his father’s death, Luke, driven by a deeper spiritual calling, chose the path of a hermit, much to his mother’s dismay who had hoped for a more conventional life for him. His journey in pursuit of this calling was not easy; he was once mistakenly captured by tribesmen who thought he was a runaway slave and subsequently imprisoned.

After his release and return home, Luke faced ridicule for his failed attempt to leave. However, his fate took a turn when two monks journeying to the Holy Land convinced his mother to let him join a monastery in Athens. His stay there was short-lived, as his superior sent him back home, citing a vision of his mother needing him.

Over time, his mother came to understand and accept his religious vocation. Luke then established his hermitage on Mount Joannitsa, near Corinth. He became renowned for his holiness and the miracles attributed to him, earning him the title of a “miracle worker.” His popularity continued to grow, and following his death, his cell was transformed into an oratory.

Photo credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Saint Luke the Younger appeared first on uCatholic.

Daily Reading

Saturday of the Fourth Week in Ordinary Time

Reading 1 1 Kings 3:4-13 Solomon went to Gibeon to sacrifice there,because that was the most renowned high place.Upon its altar Solomon offered a thousand burnt offerings.In Gibeon the LORD…

Daily Meditation

Called to Journey

Click here for daily readingsAt the end of a long journey, we can feel both exhaustion and fulfillment. Imagine the Apostles’ feeling of encouragement and achievement as they gather back…