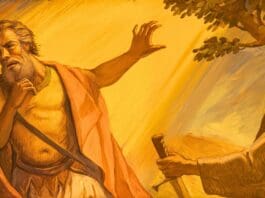

Saint Thomas Aquinas is celebrated not only as a priest and doctor of the Church but also as the patron saint of universities and students. His feast day takes place on January 28th.

Born into nobility in 1226 as the son of Landulph, Count of Aquino, Thomas was entrusted to the Benedictines of Monte Casino at the tender age of five. His early education there left his teachers astounded by his remarkable intelligence and piety, surpassing his peers in both academics and virtue.

As he matured, Thomas made a decisive turn away from worldly pursuits, choosing to embrace a religious life. In 1243, at seventeen, he encountered resistance from his family as he joined the Dominicans of Naples. His family’s relentless efforts to deter him, including the temptation with an impure woman, were futile against his steadfast resolve. Thomas’s unwavering commitment to his vocation was believed to be divinely honored with the gift of perfect chastity, earning him the title of the “Angelic Doctor.”

In his academic journey, Thomas studied under the esteemed St. Albert the Great in Cologne, where, despite his quiet demeanor and imposing stature earning him the moniker “dumb ox,” he shone brightly as a student. By twenty-two, he was already teaching in Cologne and began publishing scholarly works. A move to Paris saw his reputation flourish, and at thirty-one, he achieved his doctorate.

His time in Paris was marked not only by academic achievements but also by his notable association with King St. Louis. His scholarly journey took a significant turn when Urban IV summoned him to Rome in 1261, though Thomas declined any ecclesiastical honors offered to him. Renowned for his prolific writing, Thomas’s works, including the unfinished “Summa Theologica,” fill twenty volumes, distinguished by their intellectual depth and clarity.

Despite being offered high ecclesiastical positions, like the archbishopric of Naples by Clement IV, Thomas remained devoted to his scholarly and preaching missions. His journey concluded at the Cistercian monastery of Fossa Nuova in 1274, where he passed away en route to the second Council of Lyons.

Saint Thomas Aquinas’s theological contributions have left an indelible mark on the Church.

He was canonized in 1323 and declared as Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius V.

Editorial credit: Zvonimir Atletic / Shutterstock.com

The post Saint Thomas Aquinas, Doctor of the Church appeared first on uCatholic.

Daily Reading

Saturday of the Fourth Week in Ordinary Time

Reading 1 1 Kings 3:4-13 Solomon went to Gibeon to sacrifice there,because that was the most renowned high place.Upon its altar Solomon offered a thousand burnt offerings.In Gibeon the LORD…

Daily Meditation

Called to Journey

Click here for daily readingsAt the end of a long journey, we can feel both exhaustion and fulfillment. Imagine the Apostles’ feeling of encouragement and achievement as they gather back…