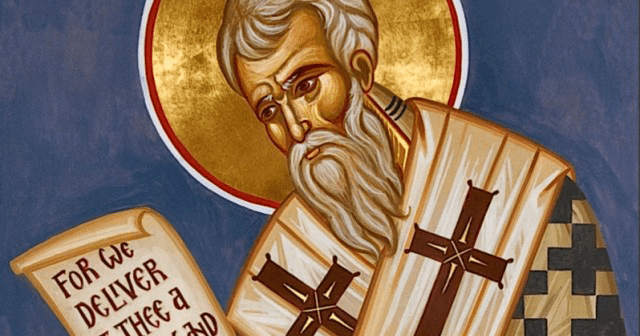

Cyril of Jerusalem, born around 315, witnessed the rise and fall of Arianism within his lifetime, navigating the tumultuous ecclesiastical politics that marked his era. Raised in Jerusalem by Christian parents, Cyril’s early exposure to the city’s sacred sites, pre-renovation, suggests a deep familial and local grounding in his faith. His writings reveal a man deeply concerned with parental respect and familial bonds, extending this care to his sister and nephew, Gelasius, who later achieved sainthood.

Cyril belonged to the Solitaries, a community dedicated to chastity, asceticism, and service, living within urban confines yet apart from its secular engagements. His ecclesiastical journey began as a deacon, progressing to priesthood, under the stewardship of Bishop Maximus. Maximus entrusted him with the catechumen’s education, a role that preserved Cyril’s teachings through congregational notes.

His teachings often navigated the complex discourse around the Divine, arguing for a moderate engagement with incomprehensible mysteries, likening it to partaking in the nourishment of a vast garden without the need to consume all its fruits. This analogy underscored his approach to the divine: seek to honor, not define.

Cyril’s elevation to bishop followed Maximus’s death, a decision mired in controversy due to Arian sympathies attributed to his consecration by Acacius, the Arian bishop of Caesarea. Despite suspicions from both orthodox and Arian factions, Cyril charted a middle course, ultimately defining his legacy apart from these affiliations.

A famine during his tenure tested Cyril’s resolve, prompting him to sell church goods for relief efforts, a decision met with controversy yet reflective of his prioritization of human life over material possessions. This act, while saving many, entangled him in accusations of mismanagement and impropriety, leading to a dispute over jurisdiction with Acacius. The conflict centered not on doctrine but on the authority over Jerusalem, igniting a series of exiles and councils that saw Cyril defending his position and the orthodoxy of his teachings.

Despite being banished multiple times, Cyril’s resilience was evident in his return to Jerusalem under Emperor Julian’s edict, which sought to destabilize the Church by reinstating exiled bishops, irrespective of their doctrinal leanings. Cyril’s later years were marked by further exile and return, navigating through ecclesiastical and imperial politics until the Council of Constantinople in 381. This council vindicated Cyril, condemned Arianism, and recognized his steadfast opposition to heretical views.

Cyril’s final years, post-council, were a period of relative peace in Jerusalem, allowing him to continue his pastoral and theological work until his death in 386. His life, emblematic of the era’s religious strife, reflects a steadfast commitment to orthodoxy, familial duty, and the welfare of his community, hallmarks of his legacy as a defender of faith amidst the vicissitudes of theological and political turbulence.

Photo credit: Morphart Creation / Shutterstock

The post Saint Cyril of Jerusalem appeared first on uCatholic.

Daily Reading

Thursday of the Second Week of Advent

Reading I Isaiah 41:13-20 I am the LORD, your God, who grasp your right hand; It is I who say to you, “Fear not, I will help you.”…

Daily Meditation

Searching for the Lost One

Click here for daily readings In today’s Gospel we hear, “What is your opinion? If a man has a hundred sheep and one of them goes astray, will he not…