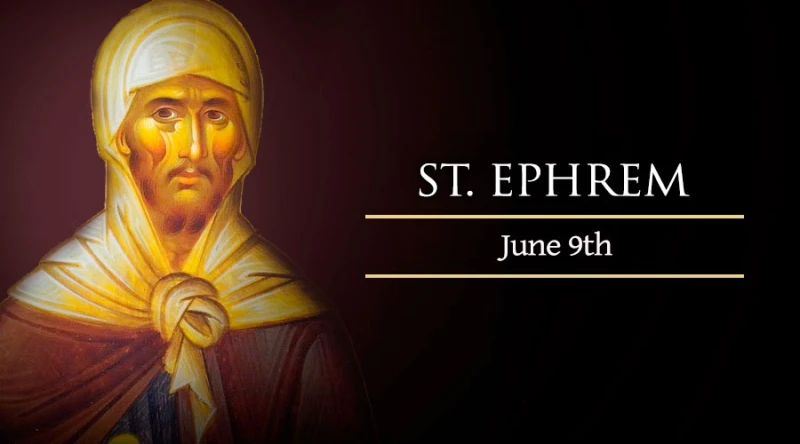

St. Ephrem

Feast date: Jun 09

On June 9, the Roman Catholic Church honors Saint Ephrem of Syria, a deacon, hermit, and Doctor of the Church who made important contributions to the spirituality and theology of the Christian East during the fourth century.

Eastern Catholics and Eastern Orthodox Christian celebrate his feast on January 28. Ephrem is especially beloved in the Syriac Orthodox Church, and counted as a Venerable Father (i.e., a sainted Monk) in the Eastern Orthodox Church. His feast day is celebrated on 28 January and on the Saturday of the Venerable Fathers. He was declared a Doctor of the Church in the Catholic Church in 1920.

In a 2007 General Audience on St. Ephrem’s life, Pope Benedict XVI noted that St. Ephrem became known as the “Harp of the Holy Spirit,” for the hymns and writings that sang the praises of God “in an unparalleled way” and “with rare skill.”

Ephrem was born in the city of Nisibis in approximately 306. Traditions differ on the question of his family background, with some sources attesting that his father was at one time a pagan priest. Other sources suggest that his family either was, or later became, entirely Christian.

Ephrem received baptism and began to consider the salvation of his soul more seriously. He embraced an ascetic lifestyle under the direction of an elder, who gave him permission to live as a hermit. Ephrem supported himself with manual labor, making sails for ships, while living in a remarkably austere manner with few comforts and little food.

Ephrem’s spiritual director and friend, Bishop James of Nisibis, died in 338. Soon after, Ephrem left his solitude and moved to Edessa in present-day Turkey. Ordained as a deacon in Edessa, he was known for sermons which combined articulate expressions of Catholic orthodoxy with urgent and fruitful calls to repentance.

The deacon was also a voluminous author, producing commentaries on the entire Bible as well as the theological poetry for which he is best known. Ephrem used Syriac-language verse as a means to explain and popularize theological truths, a technique he appropriated from others who had used poetry to promote religious error.

Late in his life, the deacon made a pilgrimage to the city of Caesarea, where God had directed him to seek the guidance of the archbishop later canonized as Saint Basil the Great. Basil helped Ephrem to resolve some of his own spiritual troubles, giving him advice which he would follow as he spent his final years in solitary prayer and writing.

Near the end of his life, Ephrem briefly left his hermitage to serve the poor and sick during a famine. His last illness came in 373, most likely from a disease he contracted through this service.

When his own death approached, he told his friends: “Sing no funeral hymns at Ephrem’s burial … Wrap not my carcass in any costly shroud: erect no monument to my memory. Allow me only the portion and place of a pilgrim; for I am a pilgrim and a stranger as all my fathers were on earth.”

St. Ephrem of Syria died in June of 373. Soon after his death, he was remembered in a public address by his contemporary Saint Gregory of Nyssa, who closed his remarks by asking Ephrem’s intercession.

“You are now assisting at the divine altar, and before the Prince of life, with the angels, praising the most holy Trinity,” said Gregory. “Remember us all, and obtain for us the pardon of our sins.”

Daily Reading

The Seventh Day in the Octave of Christmas

Reading I 1 John 2:18-21 Children, it is the last hour; and just as you heard that the antichrist was coming, so now many antichrists have appeared. Thus we know…

Daily Meditation

There Is More to Christmas

Click here for daily readings Jesus the Christ, the Light of the world, the true Light of the world that pushes back the powers of darkness, lives and reigns! Christmas…